Bhubaneswar: Over the past decade, Odisha has witnessed a troubling acceleration in climate indicators. According to data from the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD), the state's average annual temperatures have risen approximately 1.2°C since 2014—significantly higher than the global average of 0.8°C during the same period. The trend is even more pronounced in urban centers like Bhubaneswar, where temperatures have increased by 1.5°C, partly due to the urban heat island effect.

"The warming trend in Odisha is unmistakable and concerning," says Dr. Sujata Mishra, climate scientist at the Indian Institute of Climate Studies in Bhubaneswar. "What's particularly alarming is not just the rise in average temperatures but the frequency and intensity of extreme heat events."

In 2023, Odisha recorded 32 days where temperatures exceeded 40°C, compared to an average of 15-18 such days annually in the early 2010s. Titlagarh, often called Odisha's heat chamber, recorded a searing 47.5°C in May 2024, approaching its all-time high of 50.1°C set in 1998.

The human toll of this warming is substantial. Health department data indicates heat-related illnesses and fatalities have increased by approximately 35% since 2015. In 2023 alone, over 180 heat-related deaths were reported across the state.

Beyond rising temperatures, Odisha's rainfall patterns have grown increasingly erratic. Traditional monsoon predictability, crucial for the state's predominantly agricultural economy, has been disrupted. IMD data shows a 12% decrease in overall monsoon rainfall since 2014, but with dramatic increases in single-day precipitation events—creating a paradoxical situation where Odisha simultaneously faces both severe droughts and catastrophic floods.

"We're seeing longer dry spells punctuated by extremely intense rainfall events," explains Rajesh Pattnaik, a meteorologist with the Regional Meteorological Centre in Bhubaneswar. "This creates a hydrological whiplash effect that's particularly challenging for agriculture and water management."

The coastal districts face additional threats from rising sea levels. Tide gauge data from Paradip and Puri shows sea levels rising at approximately 3.5 mm per year—higher than the global average of 3.1 mm. This has accelerated coastal erosion, affecting over 140 kilometers of Odisha's coastline.

In coastal villages like Satabhaya, which has already lost two-thirds of its original land to the sea, climate change isn't an abstract concept—it's an existential threat. Over 200 families have been permanently displaced, becoming climate refugees in their own state.

"My ancestors lived here for generations, but the sea has taken everything," says 62-year-old Niranjan Behera, who was forced to relocate from Satabhaya to a government rehabilitation colony 10 kilometers inland. "Our temple, our farms, our history—all underwater now."

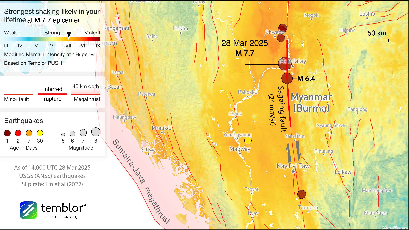

The climate crisis is also intensifying Odisha's vulnerability to cyclones. While the state has dramatically improved its disaster response since the devastating 1999 super cyclone that claimed over 10,000 lives, the increasing frequency and intensity of cyclonic storms pose new challenges. Between 2018 and 2023, Odisha experienced five major cyclones (Titli, Fani, Bulbul, Amphan, and Yaas), compared to eight in the entire preceding decade.

Ocean temperature data from the Bay of Bengal shows warming of approximately 1°C in the past decade, providing additional energy for cyclone formation and intensification. Climate models project that by 2050, the likelihood of severe cyclones affecting Odisha could increase by up to 40%.

The climate crisis is also altering Odisha's ecosystems. The Chilika Lake, Asia's largest brackish water lagoon and a wetland of international importance, has seen salinity changes and shrinking water spread due to altered rainfall patterns and rising sea levels. This threatens both biodiversity and the livelihoods of over 200,000 fishers who depend on the lake.

The state government has begun responding to these challenges. In 2018, Odisha became one of the first Indian states to develop a comprehensive Climate Change Action Plan. The state has invested in early warning systems, constructed multi-purpose cyclone shelters, and launched reforestation initiatives aimed at creating carbon sinks while protecting against soil erosion.

"We're transitioning from disaster response to disaster risk reduction and climate adaptation," says Bishnupada Sethi, Special Relief Commissioner of Odisha. "But the scale of the challenge requires significant resources and technical capacity."

The state has also embraced renewable energy, with installed solar capacity increasing from just 87 MW in 2015 to over 650 MW today. However, this represents only a fraction of Odisha's energy mix, which remains heavily dependent on coal.

Agricultural adaptation efforts include promoting drought-resistant crop varieties, water conservation techniques, and alternate livelihood options for farmers in climate-vulnerable regions. However, implementation challenges remain, particularly in reaching small and marginal farmers who make up the majority of Odisha's agricultural workforce.

As global temperatures continue to rise, Odisha's climate challenges will likely intensify. Climate models project the state could warm by an additional 1.5-2.5°C by 2050, with corresponding increases in extreme weather events, sea-level rise, and ecosystem disruption.

For millions of Odishans, climate change is already reshaping lives and livelihoods, and the coming decades will require unprecedented adaptation efforts. As one of India's most climate-vulnerable states, Odisha's experiences offer important insights into the challenges that many regions will face in a warming world—and the urgency of both mitigation and adaptation measures.